Living in a museum – Space for identity?

Ancient tombs, modern dwellers: Investigating the relationship of archaeological sites to contemporary communal identity in al-Qurna, Thebes (Egypt)

Over two hundred years of western archaeological exploration, motivated by political and economic gain alongside research, have focused on the creation of an ideational space in which ancient and modern Egypt are two separate, hermetically sealed entities. Providing western “experts” with privileged access to research on the ancient Egyptian past, living Egyptians have been denied identification with this history due to the “diluting” cultural influence of the coming of Islam in the mid-seventh century CE. Positioning the communities living within and nearby archaeological sites as mere adjunct to archaeological research means that the interpretations and perspectives of these individuals, to whom the past is an integral part of their daily lives, are effectively written out of history. Influenced by western academia and heritage tourism, the Egyptian government has likewise played a significant role in the formation of this divisive social history to the extent that communities living in close proximity to archaeological sites have also been physically obscured from these areas. For example, a nine metre high wall was built to separate the inhabitants of Nazlet al-Simman from the Giza Necropolis.

Nazlet al-Simman & Giza pyramids: Modern city meets ancient necropolis – 70,000 undesirables, public domain WikiCommons

Different use(r)s – different interests

Another case study which reveals this form of “space governance” and the devaluing of contemporary relationships with ancient sites is the area of Serabit al-Khadim, where the government proposed dismantling the temple of Hathor, a site of great significance to the local Bedouins, to relocate it to a museum in Sharm el-Sheikh.

Sign in old Al-Qurna, public domain WikiCommons

While such developments reveal how ancient Egypt is viewed as detachable from today’s social landscape and wider social history by national governments and foreign academics alike, those actually living in and among archaeological sites have developed their own highly integrated cultural narratives which place the past physically, spiritually and mythically at the heart of modern collective identities. Thus, the dichotomy between Egyptian communities and the government and between Egyptians and outsiders reveals the need for academic research that challenges lingering orientalist ideologies of difference in order to create a balance between the tangible and intangible history of archaeological sites and their meaning to diverse stakeholders in the present.

The project aims to investigate the uses, meanings, inter-relationships and experiences of multiple stakeholders (i.e. local communities, archaeologists, tourists), which revolve around one specific archaeological site: the Theban Necropolis in Luxor.

Through archaeological ethnography, we hope to reveal how the different interest groups perceive the heritage landscape, other “users’ of this landscape, and their interaction with each other.

Theban Necropolis, the village of Al-Qurna: farmland meets World Heritage, © Raimond Spekking

The untold story of archaeology

The work addresses the general imbalance between Egyptological and community interpretations of archaeological sites, and aims to evaluate the personal, social, political, historical and economic agendas that continue to transform perceptions of sites and contemporary communal identities. Through closely integrated tandem research, we address over 200 years of archaeological exploration which has prioritised ancient heritage, academic knowledge and perceptions of temporally isolated “space” over living communities and ignored the significance of academic output and archaeological sites on the modern social landscape and its inhabitants. The research is, therefore, essential in presenting the “untold story of archaeology” and revealing how the past does not exist in isolation but is part of a continuum of history which gives meaning to archaeological sites in the same way that the sites give meaning to local communities, academics and tourists.

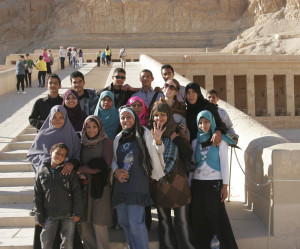

Common people – common place: Teenagers at the sacred lake, Karnack temple, Luxor City, © Hanna/Tully

The pursuit of knowledge about the ancient Egyptian past has traditionally ignored the role that the heritage from which this past is reconstructed plays in the formation and sustenance of contemporary Egyptian identities. This research aims to better understand this intricate web of interrelationships through the development of two interconnecting collaborative projects, which explore intangible heritage in the area of al-Qurna, on the west bank of the Nile in Luxor. The scattered settlements of al-Qurna, located within a World Heritage listed landscape of the Theban Necropolis, provide the focus for study because the clearly delineated space is both densely packed with some of Egypt’s most treasured archaeological remains and because the site has provided a constant source for negotiation between inhabitants, Egyptologists and governments for more than 150 years.

Al-Qurna – a “lived” social landscape

© Hanna/Tully

© Hanna/Tully

Representing the way in which the residents of al-Qurna are affected by the archaeology which shapes their daily lives is essential to understanding the continuing importance of archaeological “spaces”, beyond the realm of the economy of tourism, within modern Egyptian society. By combining social anthropology with the investigation of the archaeological, ethnographic, travelogue and media sources pertaining to the area, from historical research to the present, the way in which different interest groups construct archaeological sites and the impact of these constructions in shaping academic knowledge and collective identities is being revealed. The exploration of the perceptions and the impact that tourists, archaeologists and other groups, visiting and working in the area, have of the Qurnawis and their place among the Theban Necropolis is integral to these goals to provide a wider context for the research by enabling comparisons to be made between local and foreign communities, and between domestic, academic and leisure based stakeholders in the area. Joint publication of the methodologies, findings and outcomes of the project will consolidate the research with the fundamental aim of promoting the importance of the “lived” social landscape to the future of archaeological practice in Egypt and beyond.

Dr Gemma E. Tully & Dr Monica Hanna about their project

“The project came about as we had corresponded, via email, regarding collaborative archaeological work in Egypt during our PhD research. We soon realised that we had similar aims and saw the Topoi research opportunity with E-CSG-V (Topoi 1) as the ideal platform to develop our work as an international partnership.

The Topoi ethos is very much in keeping with our own cross-disciplinary research beliefs and goals. We would very much like to remain affiliated with the excellence cluster as it provides the opportunity to push boundaries within the archaeological field and to draw upon the expertise of scholars from other related disciplines. We hope to publish our current research in a monograph, in English and Arabic, and would ideally like to extend the work to future field seasons to consolidate the work that has been done and develop it further. Research in this field needs to be properly promoted to different academic communities: Archaeologists, Egyptologists, Anthropologists, Sociologists and so on. Thus, continuing our partnership with Topoi would give us time to achieve this, as well as to develop our methodologies and to continue to document the shifting role of archaeological sites within contemporary Egyptian society. ”

What is the most important finding of your studies so far?

public domain WikiCommons

“The complexity of relationships: social, cultural, economic, personal, political, local, international, which surround the Theban Necropolis has been extremely enlightening. However, what is perhaps most important is building a picture of how different stakeholders perceive other user groups and how the lack of communication, knowledge exchange and mutual understanding impacts negatively on all those who visit, live or work in close proximity to the archaeology.

Smaller findings along the way were very interesting, such as understanding better the intricate relationship communities have with their own heritage and how this can be built on to develop better collaboration between all the stakeholders. In the future, the collaborative approach could bridge the gap between the different disciplines involved in the wide arena of Egyptian heritage and help situate innovative academic studies in new field practice.”

Final chord

© Hanna/Tully

“Our work is very much “of the moment’. Egypt is in a state of flux and we can only hope to capture these dynamics in the here and now. Therefore, we see the project as documenting the socio-economic impact that the Theban Necropolis has on the area at an important moment of change. The forthcoming monograph will outline the situation in the present and will hopefully provide a useful source of comparison with future heritage policy, social change and further ethnographic work.”