This project explored the question of what factors led to an imperial building project being judged as megalomaniacal or not. The research project then focused particularly on Imperial Rome and builds on the Palatine Hill project (DAI).

Research

Megalomania is a term that appears repeatedly in the body of research on the building projects of Roman emperors. Yet the basis for this appraisal remains remarkably vague. The Baths of Caracalla, for instance, are regarded as the expression of the megalomaniacal traits of the ruler, while other equally large baths are not. When is a thermal bath an expression of megalomania and when is it an expression of imperial duty and normal actions, as Zanker formulates in the concept “The emperor builds for the people”? What is XXL in the context of imperial construction, and from what point on is it standard?

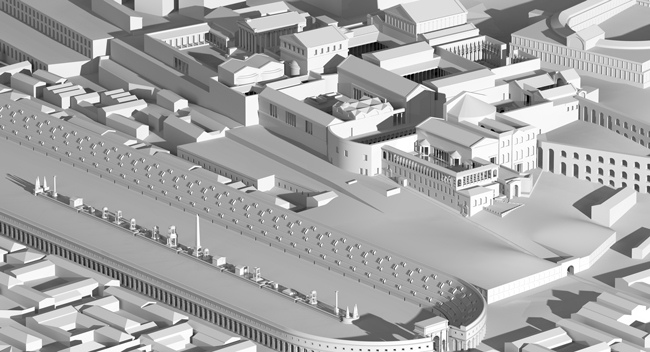

A number of appraisals of imperial building projects are based on existing ancient judgments. For example, the individual expansion phases of the palaces of the Roman emperors were already varyingly appraised in ancient times, something which has seldom been critically questioned in the research so far. The gigantic extension of the palace into an enormous villa landscape under Nero was regarded as megalomaniacal. The monumentality of the Domus Aurea is thereby measured not so much by the use of precious materials or the luxurious design of the palace rooms. Of far greater importance was the vast extension of the area claimed for the project in the densely built city of Rome and the sums spent on redesigning the site that were clearly felt to stand out from the norm. Even if statements by ancient writers from antiquity certainly cannot be regarded as representing the opinion of the antique observer, they do indicate that the extension of Nero’s palace complex could be understood as being monumental in the negative sense of the word. Domitian’s palace is judged very ambivalent. On the one hand it is compared with the building lust and pomposity of a Croesus and therefore negatively due to its scale and luxuriousness. By other poets the giddying heights of the palace in particular were emphasised and the extent of the complex this time in a positive sense is regarded as being monumental. In light of the vast extent of the area covered by the building within the city and the architecturally ‘monumentalisation’ of the hill in comparison with other sacred and important public buildings at Rome, the imperial palaces must have appeared to contemporaries as monumental.

Results

The precise study of the materials used for the new Flavian building, together with a clarification of the progress of construction, also permits a clearer concept of the quantity of materials that were used. According to the latest research, particularly on the construction techniques and brick stamps, it can be ascertained that in an area of approx. 96,000 m², work begun on construction at around the same time. And even if today it is also clear that when Domitian died in 96 A.D. not all of the sections had been completed, large parts of the new building must have been realised by the time of its consecration in 92 A.D., and thus within a construction period of approximately 10 years. This not only required the necessary ‘manpower’ in terms of skilled and unskilled labourers and a sufficient number of work animals for transportation, but an adequate flow of supplies of construction materials also needed to be maintained. The provision of such huge quantities of building materials must also have permanently altered the cityscape of Rome. The materials, such as travertine, brick, basalt, etc. had to be transported from the surrounding area from up to 80 km away. The provision of the enormous quantities of building materials for extending the imperial palaces accordingly required a smooth, efficiently functioning logistical process by establishing manufacturing facilities on an industrial level. It can be verified that for the realisation the increasing imperial influence on the production of building materials was an important factor. For example the production of bricks became an outright monopoly of the imperial dynasty. A monopolisation of the construction material used thus created a large economic power factor for the Roman building industry. The building of the monumental complexes in ancient Rome is signified both a technological and a symbolic change in the Roman building tradition.

The results of the project have been published in several publications and the research data collection:

Die Ziegelstempel der kaiserlichen Palastanlagen auf dem Palatin in Rom